GLENN COLQUHOUN

Gallery

From Myths and Legends of the Ancient Pākehā - expected 2024

In 2012 New Zealand was the Country of Honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair. I was asked to write for the occasion using the Transit of Venus, observed that year, as a starting point. For me the transit had always been a motif for interaction between Europe and Polynesia; observing it in 1769 was one of the reasons Cook first came to the South Pacific. Although I have a great-great-great-grandfather from Westphalia, Germany had never felt like a country New Zealand had much of a relationship with, unless it was one of conflict, and so I went searching for stories of connection. Eventually I stumbled on Dieffenbach. For some reason I liked him. He seemed kind and intense and lost.

What really settled things for me, however, was the fact that we were both doctors. For a number of years I worked for an iwi health provider that served the people of Te Āti Awa ki Whakarongotai on the Kāpiti Coast. Aunty Kate had been one of my patients there. In 1839 Dieffenbach assisted the wounded at the battle of Kūititanga which took place between Te Āti Awa and Ngāti Raukawa-ki-te-Tonga around the Waikanae river mouth. It is not difficult to believe that he may have come across Te Kahutatara, or her father Te Pukerangiora, or his father Te Heke, that day. All of them were at the battle. And all of them were direct ancestors of Aunty Kate. Whakapapa doesn’t only connect those who are related, it connects all those who brush up against it. I like to think this is what shivered through me when I stumbled across Dieffenbach. It is not such a stretch to think that he and I have cared for the same skin.

***

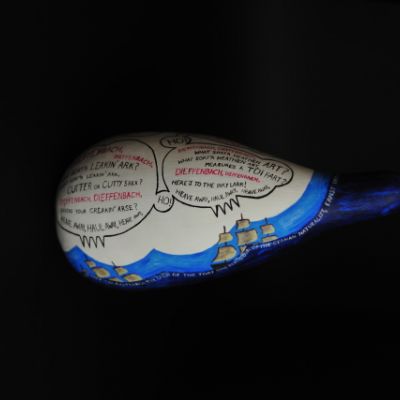

Above all else, the poems have a specific purpose based on the Māori custom of the kawe mate. This custom involves returning the spirit of a person to the place where they belong after they have died, especially if that person has been important to a particular people. Often a photograph of the individual is carried by the people he or she was important to and placed in their tribal meeting house. Gourds were used in the past by Māori as containers, and as musical instruments and vessels to hold incantations, and were often decorated. Each poem in this sequence has been hand-painted onto a gourd that was then blessed by Te Āti Awa ki Whakarongotai. The gourds and the songs they contain were then taken back to Germany. They rest now at the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum of World Cultures in Cologne, where a large collection of Dieffenbach memorabilia is held.

I wrote about Dieffenbach using the forms I did because I wanted both traditions of poetry in New Zealand to sit beside each other on the page. I wanted to show that our literature in English can be invigorated by its engagement with an oral tradition. Much is made about how Europe has made an impact on Māori but I wanted to show that Māori have also made an impact on Europe. I wanted these poems to look as if an oral tradition had breathed into them on the paper and made them fat. Over time the project became some sort of poetic CPR.

From 1839 to 1841 Dieffenbach lived in New Zealand and became our first resident Pākehā scientist. He surveyed the Marlborough Sounds and Wellington. He met Te Rauparaha on Kāpiti the day the battle of Kūititanga raged, and was the first European to climb Taranaki, boiling water on the summit to estimate its height. He sailed to Northland, then passed by foot in a giant loop from Auckland through the centre of the North Island, keeping a pet weka for much of the way. He spent time in New South Wales and the Chatham Islands and collected and recorded as he went. He coined the term ‘greywacke’ for the rock that forms the backbone of New Zealand. He collected a sample of the mountain buttercup specific to Taranaki, Ranunculus nivicola. He gave his name to the Chatham Island rail, now extinct, Gallirallus dieffenbachii. And he completed the second grammar ever written of Te Reo Māori.

In 1841 Dieffenbach returned to London. His experiences with Māori had moved him and he increasingly warned of the impact on them of European settlement. He wrote a prescient essay on the drawbacks of colonisation for Māori. He tried to raise the money to return to the country by himself but was unable to do so. In 1843 he published his journals, a two-volume work entitled Travels in New Zealand. And in 1846 he returned to Giessen University where he eventually became the professor of geology. He married, had two daughters, contracted typhus and died in 1855.

If you cross from Wellington to Picton on the Cook Strait ferry you will pass a small headland named after Dieffenbach in the Tory Channel. His books can be tracked down occasionally in the odd second-hand bookshop. But that’s about all you will find of him these days. Few people have heard of him in New Zealand or Germany. And because of all of this, I wrote him some songs. They were one way of saying that this son of Germany is also a son of New Zealand.